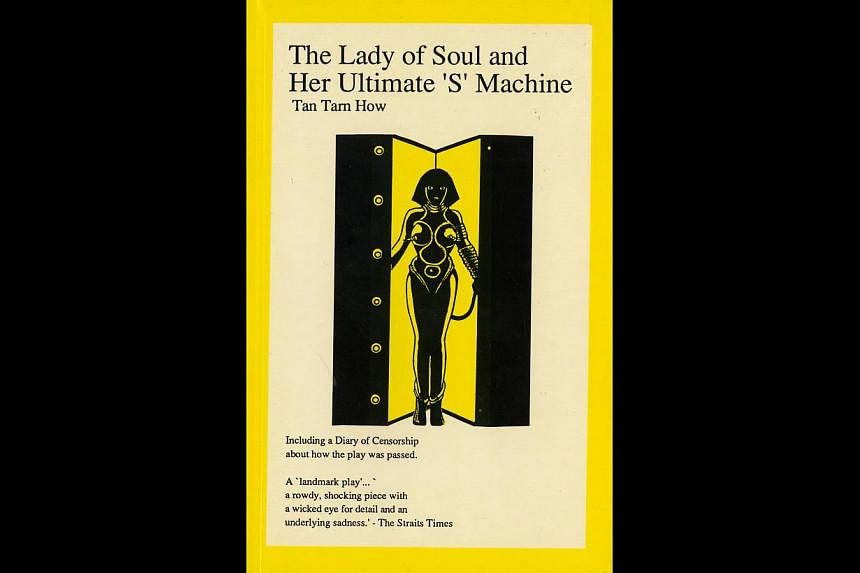

Play: The Lady Of Soul And Her Ultimate 'S' Machine (first reading in January 1992, full staging from January to February 1993)

Playwright: Tan Tarn How

What it is about: An unnamed nation (or a thinly veiled Singapore) is in search of "soul", and civil servant Derek is tasked with soul-searching as part of the Committee For The Creation Of A Vibrant Nation. The three finalists are a communist, a supporter of the arts and a mama-san, the titular "lady of soul".

In 1992, when the police's Public Entertainment Licensing Unit (Pelu) received for vetting Tan Tarn How's rollicking satirical script about a government agency's carefully calibrated attempts to inject culture into a nation, they were not particularly amused by its contents.

The script included civil servants breaking into raucous vaudeville acts, a blow-up sex doll, a side-splitting number of committees and subcommittees dealing with bureaucratic minutiae, and a past romantic relationship between a minister of state and a committee chairman, both male.

The script came back from the police - then the body responsible for arts licensing, a task that now falls on the Media Development Authority - with objections to material in 36 of its 67 pages, including: that Singapore is a nation without soul; that the play promotes sex and communism; that the play ridicules past committees as inefficient; that politicians were more interested in winning votes than delivering on promises.

In Tan's detailed "diary of censorship", appended to the first publication of Lady Of Soul in 1993, his despair is palpable: "The news is bad... Very inconsistent cuts. Enough to maul the script. Very depressed."

Director Ong Keng Sen had plans to stage Lady Of Soul within the year. Now, that seemed unlikely.

Tan, 54, was not the first playwright to grapple with censorship in Singapore, nor would he be the last. But the years 1992 to 1994 were pivotal ones in the quest for freedom of artistic expression. Lady Of Soul tested the system and heralded the first wave of adjustments to censorship rules.

The National Arts Council was set up in 1991 to advocate for the arts, and shortly after, the Censorship Review Committee, headed by the council's then chairman Professor Tommy Koh, convened for the first time. It recommended greater artistic freedom for artists and limited self-regulation for established theatre groups.

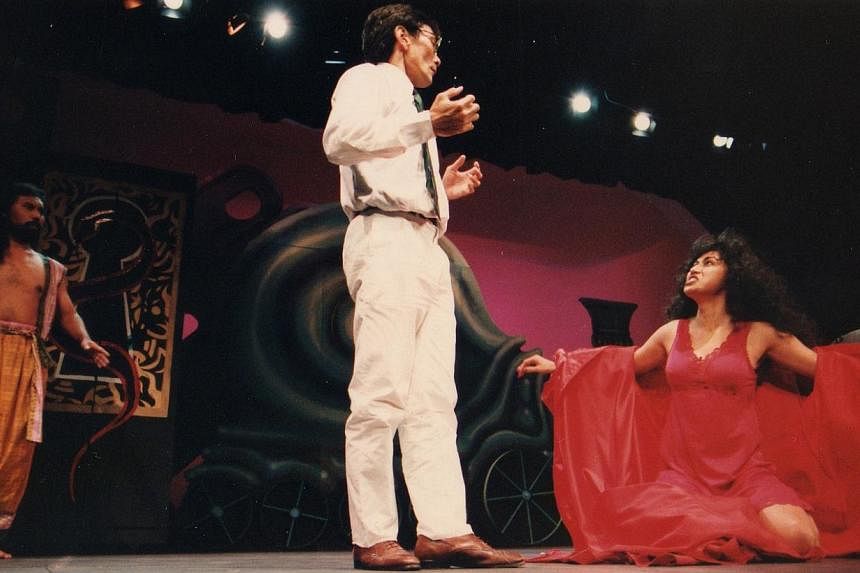

Tan had written the play as part of TheatreWorks' pioneering Writers' Lab, set up to develop home-grown writing for the stage. TheatreWorks was one of the first professional theatre companies here, responsible for many groundbreaking works. Its artistic director, Ong, who also directed Lady Of Soul, was excited by the political bent of Tan's work: "So little had been said about the political system and now he was literally churning it out. It was almost as if this fountain had opened up and the water was gushing out." Ong worked closely with Tan on shaping the work and battling the censorship that enveloped it.

Actor Gerald Chew, 51, who starred as Derek in the reading and played Derek's ex-lover, minister of state Paul, in the production, later directed it for TheatreWorks' theatre retrospective, Charging Up Memory Lane (2001).

He says of the work: "I enjoyed the satire and the sense of mischievous fun that went along with it. Everyone understands that it's a version of reality that we still live today... Some of the long passages were more didactic, but back then, it needed to be said, done and pointed out."

Chew adds that Ong was careful to ground the relationships in the play in reality, even if many of its aspects were exaggerated and "out there".

The result, as then Straits Times theatre critic Hannah Pandian wrote, was a 1993 production that marked "a watershed in Singapore theatre: it is arguably the first English play to present the country critically and artistically, without hiding behind coy allegory".

Tan's first play, Home (1992) - set in a home for the elderly - had been more naturalistic and he wanted to try dramatic devices such as satire and parody. He also wanted to find a voice for some of his frustrations as a political journalist with The Straits Times. He says: "You see what's behind the rhetoric, that they (politicians) can say one thing and perform another... So I was a bit sceptical, that even though they might want change, it is really not something which they do at all comfortably."

Tan, now a senior research fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies, went on to write at least four political plays.

He says: "There's always this question for me, which runs through my plays - what happens if you have to make a decision between saying what you think is the truth and suffering for it, versus not saying what you think."

One could say that Tan and TheatreWorks had that very same dilemma in real life. The arrests of members of the now-defunct theatre company Third Stage, for allegedly being part of the 1987 Marxist conspiracy to overthrow the Government, were still fresh in the minds of artists. There was a first reading of Lady Of Soul in January 1992, directed by Ivan Heng, whom Tan credits for helping to bring out the "comic possibilities" of the piece. Tan's wife had noticed a middle-aged man sit "grimly" through about a third of the reading before he left. Tan writes in his published diary: "She was afraid that he could be ISD; I was prepared not to be afraid, but could not help feeling a knot of fear for a while during the interval." ISD is the acronym for Internal Security Department.

He pondered this: "The play could be caught in a paradox; if they let it through without any censorship at all, then the premise of the play would be wrong, so making reasons for staging it become less intellectually compelling; if they don't, then the premise would be proven, which makes it even more important to have it staged uncensored." Interestingly, Lady Of Soul transcended this paradox by being subject first to plenty of censorship, and then no censorship at all.

In October 1992, just before Tan sent in his letter of appeal to the licensing unit, Gung-Ho Theatre Ensemble's play Too Glam One did not get a licence to be staged, reportedly because of its crude and vulgar language. It had similar themes to Lady Of Soul - it was a satire about a hypothetical future in Singapore and also poked fun at the civil service.

Miraculously enough, the second time round, Lady Of Soul was passed clean, without any cuts - a beneficiary of the revised guidelines proposed by the Censorship Review Committee. TheatreWorks was also able to stage Tan's subsequent play, Undercover (1994), set in an unspecified internal security department.

But Tan was cautious. He cites the turbulent events of 1994, including the authorities' decision to not fund the unscripted forms of performance art and forum theatre for a decade.

He says: "There was change, but it was change only up to a certain extent. We came from 'very restrictive' to 'less restrictive', but it was definitely not freedom - not even some sort of restricted freedom."

His cynicism about the political process was most recently expressed in the critically acclaimed Fear Of Writing (2011). Ong, who directed it, adds: "Sad to say, so little has changed... in a strange way, there's no redress now. If it's 'no', it's 'no'. Even though you have an appeals system, these appeals are just formalities and it is even more turgid than before."

The Lady Of Soul will be strutting back on stage next year as part of the Esplanade's SG50 celebrations and continues to echo topics that are relevant today - the desire for neat, safe categories, the push and pull between public and private life, and superficial attempts to unearth a country's heart and soul.

Tan says: "In a society which is still only partly a democracy, where the Government actively tries to control so many aspects of life, political art is definitely one of the avenues in which you can find space and get a discussion going about what is happening.

"It is a very powerful medium for raising consciousness and just reminding ourselves that there are other ways of arranging society and of leading our lives."

Follow Corrie Tan on Twitter @CorrieTan

Six Plays by Tan Tarn How, which includes The Lady Of Soul And Her Ultimate "S" Machine, is available from Epigram Books for $25.90.

The next instalment of this 15-part series will be published at the end of next month.